Evaluation has truly become a global movement. The number of evaluators and evaluation associations around the world is growing, and they are becoming more interconnected. What affects evaluation in one part of the world increasingly affects how it is practiced in another.

That is why the European standard for social impact measurement, announced just a few weeks ago, is important for evaluators in the US.

According to the published report and its accompanying press release, the immediate purpose of the standard is to help social enterprises access EU financial support, especially in relation to the European Social Entrepreneurship Funds (EuSEFs) and the Programme for Employment and Social Innovation (EaSI).

But as László Andor, EU Commissioner for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, pointed out, there is a larger purpose:

The new standard…sets the groundwork for social impact measurement in Europe. It also contributes to the work of the Taskforce on Social Impact Investment set up by the G7 to develop a set of general guidelines for impact measurement to be used by social impact investors globally.

That is big, and it has the potential to affect evaluation around the world.

What is impact measurement?

For evaluators in the US, the term impact measurement may be unfamiliar. It has greater currency in Europe and, of late, in Canada. Defining the term precisely is difficult because, as an area of practice, impact measurement is evolving quickly.

Around the world, there is a growing demand for evaluations that incorporate information about impact, values, and value. It is coming from government agencies, philanthropic foundations, and private investors who want to increase their social impact by allocating their public or private funds more efficiently.

Sometimes these funders are called impact investors. In some contexts, the label signals a commitment to grant making that incorporates the tools and techniques of financial investors. In others, it signals a commitment by private investors to a double bottom line—a social return on their investment for others and a financial return for themselves.

These funders want to know if people are better off in ways that they and other stakeholders believe are important. Moreover, they want to know whether those impacts are large enough and important enough to warrant the funds being spent to produce them. In other words, did the program add value?

Impact measurement may engage a wide range of stakeholders to define the outcomes of interest, but the overarching definition of success—that the program adds value—is typically driven by funders. Value may be assessed with quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods, but almost all of the impact measurement work that I have seen has framed value in quantitative terms.

Is impact measurement the same as evaluation?

I consider impact measurement a specialized practice within evaluation. Others do not. Geographic and disciplinary boundaries have tended to isolate those who identify themselves as evaluators from those who conduct impact measurement—often referred to as impact analysts. These two groups are beginning to connect, like evaluators of every kind around the world.

I like to think of impact analysts and evaluators as twins who were separated at birth and then, as adults, accidentally bump into each other at the local coffee shop. They are delighted and confused, but mostly delighted. They have a great deal to talk about.

How is impact measurement different from impact evaluation?

There is more than one approach to impact evaluation. There is what we might call traditional impact evaluation—randomized control trials and quasi-experiments as described by Shadish, Cook, and Campbell. There are also many recently developed alternatives—contribution analysis, evaluation of collective impact, and others.

Impact measurement differs from traditional and alternative impact evaluation in a number of ways, among them:

- how impacts are estimated and

- a strong emphasis on valuation.

I discuss both in more detail below. Briefly, impacts are frequently estimated by adjusting outcomes for a pre-established set of potential biases, usually without reference to a comparison or control group. Valuation estimates the importance of impacts to stakeholders—the domain of human values—and expresses it in monetary units.

These two features are woven into the European standard and have the potential to become standard practices elsewhere, including the US. If they were to be incorporated into US practice, it would represent a substantial change in how we conduct evaluations.

What is the new European standard?

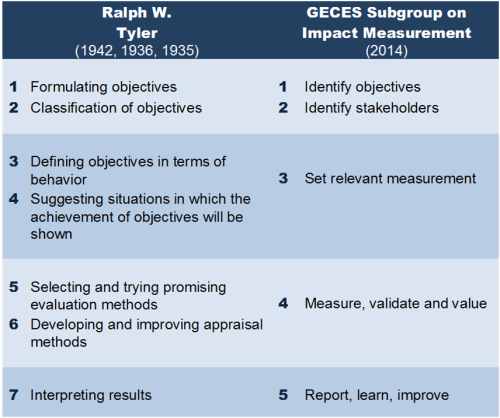

The standard creates a common process for conducting impact measurement, not a common set of impacts or indicators. The five-step process presented in the report is surprisingly similar to Tyler’s seven-step evaluation procedure, which he developed in the 1930s as he directed the evaluation of the Eight-Year Study across 30 schools. For its time, Tyler’s work was novel and the scale impressive.

Tyler’s evaluation procedure developed in the 1930s and the new European standard process: déjà vu all over again?

Tyler’s first two steps were formulating and classifying objectives (what do programs hope to achieve and which objectives can be shared across sites to facilitate comparability and learning). Deeply rooted in the philosophy of progressive education, he and his team identified the most important stakeholders—students, parents, educators, and the larger community—and conducted much of their work collaboratively (most often with teachers and school staff).

Similarly, the first two steps of the European standard process are identifying objectives and stakeholders (what does the program hope to achieve, who benefits, and who pays). They are to be implemented collaboratively with stakeholders (funders and program staff chief among them) with an explicit commitment to serving the interests of society more broadly.

Tyler’s third and fourth steps were defining outcomes in terms of behavior and identifying how and where the behaviors could be observed. The word behavior was trendy in Tyler’s day. What he meant was developing a way to observe or quantify outcomes. This is precisely setting relevant measures, the third step of the new European standard process.

Tyler’s fifth and sixth steps were selecting, trying, proving, and improving measures as they function in the evaluation. Today we would call this piloting, validation, and implementation. The corresponding step in the standard is measure, validate and value, only the last of these falling outside the scope of Tyler’s procedure.

Tyler concluded his procedure with interpreting results, which for him included analysis, reporting, and working with stakeholders to facilitate the effective use of results. The new European standard process concludes in much the same way, with reporting results, learning from them, and using them to improve the program.

How are impacts estimated?

Traditional impact evaluation defines an impact as the difference in potential outcomes—the outcomes participants realized with the program compared to the outcomes they would have realized without the program.

It is impossible to observe both of these mutually exclusive conditions at the same time. Thus, all research designs can be thought of as hacks, some more elegant than others, that allow us to approximate one condition while observing the other.

The European standard takes a similar view of impacts and describes a good research design as one that takes the following into account:

- attribution,the extent to which the program, as opposed to other programs or factors, caused the outcomes;

- deadweight, outcomes that, in the absence of the program, would have been realized anyway;

- drop-off, the tendency of impacts to diminish over time; and

- displacement, the extent to which outcomes realized by program participants prevent others from realizing those outcomes (for example, when participants of a job training program find employment, it reduces the number of open jobs and as a result may make it more difficult for non-participants to find employment).

For any given evaluation, many research designs may meet the above criteria, some with the potential to provide more credible findings than others.

However, impact analysts may not be free to choose the research design with the potential to provide the most credible results. According to the standard, the cost and complexity of the design must be proportionate to the size, scope, cost, potential risks, and potential benefits of the program being evaluated. In other words, impact analysts must make a difficult tradeoff between credibility and feasibility.

How well are analysts making the tradeoff between credibility and feasibility?

At the recent Canadian Evaluation Society Conference, my colleagues Cristina Tangonan, Anna Fagergren (not pictured), and I addressed this question. We described the potential weaknesses of research designs used in impact measurement generally and Social Return on Investment (SROI) analyses specifically. Our work is based on a review of publicly available SROI reports (to date, 107 of 156 identified reports) and theoretical work on the statistical properties of the estimates produced.

What we have found so far leads us to question whether the credibility-feasibility tradeoffs are being made in ways that adequately support the purposes of SROI analyses and other forms of impact measurement.

One design that we discussed starts with measuring the outcome realized by program participants. For example, how many participants of a job training program found employment, or the test scores realized by students who were enrolled in a new education program. Sometimes impact analysts will measure the outcome as a pre-program/post-program difference, often they measure the post-program outcome level on its own.

Once the outcome measure is in hand, impact analysts adjust it for attribution, deadweight, drop-off, and displacement by subtracting some amount or percentage for each potential bias. The adjustments may be based on interviews with past participants, prior academic or policy research, or sensitivity analysis. Rarely are they based on comparison or control groups constructed for the evaluation. The resulting adjusted outcome measure is taken as the impact estimate.

This is an example of a high-feasibility, low-credibility design. Is it good enough for the purposes that impact analysts have in mind? Perhaps, but I’m skeptical. There is a century of systematic research on estimating impacts—why didn’t this method, which is much more feasible than many alternatives, become a standard part of evaluation practice decades before? I believe it is because the credibility of the design (or more accurately, the results it can produce) is considered too low for most purposes.

From what I understand, this design–and others that are similar–would meet the European standard. That leads me to question whether the new standard has set the bar too low, unduly favoring feasibility over credibility.

What is valuation?

In the US, I believe we do far less valuation than is currently being done in Europe and Canada. Valuation expresses the value (importance) of impacts in monetary units (a measure of importance).

If the outcome, for example, were earned income, then valuation would entail estimating an impact as we usually would. If the outcome were health, happiness, or well-being, valuation would be more complicated. In this case, we would need to translate non-monetary units to monetary units in a way that accurately reflects the relative value of impacts to stakeholders. No easy feat.

In some cases, valuation may help us gauge whether the monetized value of a program’s impact is large enough to matter. It is difficult to defend spending $2,000 per participant of a job training program that, on average, results in additional earned income of $1,000 per participant. Participants would be better off if we gave $2,000 to each.

At other times, valuation may not be useful. For example, if one health program saves more lives than another, I don’t believe we need to value lives in dollars to judge their relative effectiveness.

Another concern is that valuation reduces the certainty of the final estimate (in monetary units) as compared to an impact estimate on its own (in its original units). That is a topic that I discussed at the CES conference, and will again at the conferences of the European Evaluation Society, Social Impact Analysts Association, and the American Evaluation Association .

There is more to this than I can hope to address here. In brief—the credibility of a valuation can never be greater than the credibility of the impact estimate upon which it is based. Call that Gargani’s Law.

If ensuring the feasibility of an evaluation results in impact estimates with low credibility (see above), we should think carefully before reducing credibility further by expressing the impact in monetary units.

Where do we go from here?

The European standard sets out to solve a problem that is intrinsic to our profession–stakeholders with different perspectives are constantly struggling to come to agreement about what makes an evaluation good enough for the purposes they have in mind. In the case of the new standard, I fear the bar may be set too low, tipping the balance in favor of feasibility over credibility.

That is, of course, speculation. But so too is believing the balance is right or that it is tipped in the other direction. What is needed is a program of research—research on evaluation—that helps us understand whether the tradeoffs we make bear the fruit we expect.

The lack of research on evaluation is a weak link in the chain of reasoning that makes our work matter in Europe, the US, and around the world. My colleagues and I are hoping to strengthen that link a little, but we need others to join us. I hope you will.

Running Hot and Cold for Mixed Methods: Jargon, Jongar, and Code

Jargon is the name we give to big labels placed on little ideas. What should we call little labels placed on big ideas? Jongar, of course.

A good example of jongar in evaluation is the term mixed methods. I run hot and cold for mixed methods. I praise them in one breath and question them in the next, confusing those around me.

Why? Because mixed methods is jongar.

Recently, I received a number of comments through LinkedIn about my last post. A bewildered reader asked how I could write that almost every evaluation can claim to use a mixed-methods approach. It’s true, I believe that almost every evaluation can claim to be a mixed-methods evaluation, but I don’t believe that many—perhaps most—should.

Why? Because mixed methods is also jargon.

Confused? So were Abbas Tashakkori and John Creswell. In 2007, they put together a very nice editorial for the first issue of the Journal of Mixed Methods Research. In it, they discussed the difficulty they faced as editors who needed to define the term mixed methods. They wrote:

By the first definition, mixed methods is jargon—almost every evaluation uses more than one type of data, so the definition attaches a special label to a trivial idea. This is the view that I expressed in my previous post.

By the second definition, which is closer to my own perspective, mixed methods is jongar—two simple words struggling to convey a complex concept.

My interpretation of the second definition is as follows:

A mixed-methods evaluation is one that establishes in advance a design that explicitly lays out a thoughtful, strategic integration of qualitative and quantitative methods to accomplish a critical purpose that either qualitative or quantitative methods alone could not.

Although I like this interpretation, it places a burden on the adjective mixed that it cannot support. In doing so, my interpretation trades one old problem—being able to distinguish mixed methods evaluations from other types of evaluation—for a number of new problems. Here are three of them:

These complex ideas are lurking behind simple words. That’s why the words are jongar and why the ideas they represent may be ignored.

Technical terms—especially jargon and jongar—can also be code. Code is the use of technical terms in real-world settings to convey a subtle, non-technical message, especially a controversial message.

For example, I have found that in practice funders and clients often propose mixed methods evaluations to signal—in code—that they seek an ideological compromise between qualitative and quantitative perspectives. This is common when program insiders put greater faith in qualitative methods and outsiders put greater faith in quantitative methods.

When this is the case, I believe that mixed methods provide an illusory compromise between imagined perspectives.

The compromise is illusory because mixed methods are not a middle ground between qualitative and quantitative methods, but a new method that emerges from the integration of the two. At least by the second definition of mixed methods that I prefer.

The perspectives are imagined because they concern how results based on particular methods may be incorrectly perceived or improperly used by others in the future. Rather than leap to a mixed-methods design, evaluators should discuss these imagined concerns with stakeholders in advance to determine how to best accommodate them—with or without mixed methods. In many funder-grantee-evaluator relationships, however, this sort of open dialogue may not be possible.

This is why I run hot and cold for mixed methods. I value them. I use them. Yet, I remain wary of labeling my work as such because the label can be…

Too bad—the ideas underlying mixed methods are incredibly useful.

6 Comments

Filed under Commentary, Evaluation, Evaluation Quality, Program Evaluation, Research

Tagged as abbas tashakkori, code, complexity, evaluation, evaluations, jargon, john creswell, jongar, mixed methods, qualitative and quantitative methods, research, simpicity