George Bernard Shaw quipped, “If all economists were laid end to end, they would not reach a conclusion.” However, economists should not be singled out on this account — there is an equal share of controversy awaiting anyone who uses theories to solve social problems. While there is a great deal of theory-based research in the social sciences, it tends to be more theory than research, and with the universe of ideas dwarfing the available body of empirical evidence, there tends to be little if any agreement on how to achieve practical results. This was summed up well by another master of the quip, Mark Twain, who observed that the fascinating thing about science is how “one gets such wholesale returns of conjecture out of such a trifling investment of fact.”

Recently, economists have been in the hot seat because of the stimulus package. However, it is the policymakers who depended on economic advice who are sweating because they were the ones who engaged in what I like to call data-free evaluation. This is the awkward art of judging the merit of untried or untested programs. Whether it takes the form of a president staunching an unprecedented financial crisis, funding agencies reviewing proposals for new initiatives, or individuals deciding whether to avail themselves of unfamiliar services, data-free evaluation is more the rule than the exception in the world of policies and programs. Continue reading

It’s a Gift to Be Simple

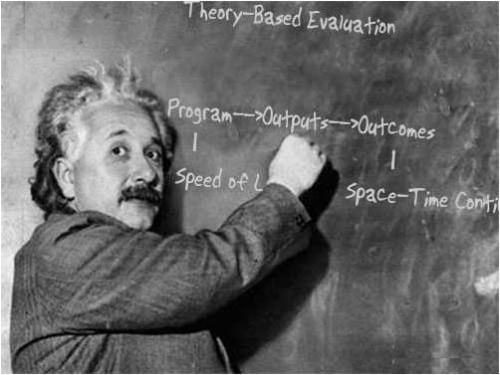

Theory-based evaluation acknowledges that, intentionally or not, all programs depend on the beliefs influential stakeholders have about the causes and consequences of effective social action. These beliefs are what we call theories, and they guide us when we design, implement, and evaluate programs.

Theories live (imperfectly) in our minds. When we want to clarify them for ourselves or communicate them to others, we represent them as some combination of words and pictures. A popular representation is the ubiquitous logic model, which typically takes the form of box-and-arrow diagrams or relational matrices.

The common wisdom is that developing a logic model helps program staff and evaluators develop a better understanding of a program, which in turn leads to more effective action.

Not to put too fine a point on it, this last statement is a representation of a theory of logic models. I represented the theory with words, which have their limits, yet another form of representation might reveal, hide, or distort different aspects of the theory. In this case, my theory is simple and my representation is simple, so you quickly get the gist of my meaning. Simplicity has its virtues.

It also has its perils. A chief criticism of logic models is that they fail to promote effective action because they are vastly too simple to represent the complexity inherent in a program, its participants, or its social value. This criticism has become more vigorous over time and deserves attention. In considering it, however, I find myself drawn to the other side of the argument, not because I am especially wedded to logic models, but rather to defend the virtues of simplicity. Continue reading →

Leave a comment

Filed under Commentary, Evaluation, Program Evaluation

Tagged as beliefs, complexity, evaluation, evaluations, Program Evaluation, simplicity, theory-based evaluation